From bunraku puppet theater to kabuki classical drama, Osaka is home to a range of different living, breathing forms of traditional performance art. Among these, Kamigata rakugo is one in particular that offers fun and laughter along with chances to learn about the dialect and culture of the Kamigata area centered around Osaka and Kyoto, a form of traditional performance with an air of casual informality. And the mecca of this traditional storytelling art can be found at a theater called the Tenma Tenjin Hanjotei. Let’s unravel the fascinating charms of Kamigata rakugo with an actual trip to this yose theater.

Visiting the Sole Theater Dedicated to Kamigata Rakugo

This Tenma Tenjin Hanjotei theater was in fact built 15 years ago — a surprisingly brief history. Before its opening, there did exist the Yoshimoto and the Shochiku-za theaters, and a performance hall run by Beicho Office would put on rakugo shows. Yet there was no permanent venue where rakugo could be enjoyed all the time. Then the Kamigata Rakugo Association, aiming to make a comeback 60 years after the end of the war, set to work. In 2006, they came to build a yose theater on a site supplied by the shrine just outside the torii gate at the north entrance to the Osaka Temmangu Shrine.

Curiously, the environs of the theater had once been called Tenma Hachiken and been thronged with yose theaters and shibai-goya playhouses. One of these, a playhouse called the Daini Bungeikan is said to have been the birthplace of the Yoshimoto Kogyo entertainment conglomerate.

What Distinguishes the Kamigata and Edo Schools of Rakugo

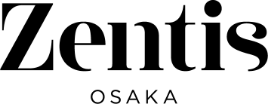

First off, we turned to Jinchi Shofukutei, head of the Kamigata Rakugo Association, for a lesson in what sets Kamigata rakugo — performed in the Kamigata region centered around Osaka and Kyoto — from the Edo rakugo staged primarily in Tokyo.

“To start out with, Kamigata rakugo and Edo rakugo spring from different sources. Both have their origins in the mid-Edo period (around the early 18th century), but while the Edo version was a sort of parlor performance that would be presented to guests who’d been invited to receptions, the Kamigata version began on the grounds of the Ikukunitama Shrine, where storytellers would get hold of passersby and present stories to them, expecting donations. So, in the days when rakugo had just come into being, the audience in Edo was virtually all male, whereas in Kamigata, it was a mix of men and women of all ages. Also in terms of the content, Edo rakugo featured a lot of moralistic tales with samurai warriors as protagonists, while Kamigata rakugo mainly dealt with the lives of ordinary people. That, I think, is why it feels more approachable and accessible even to beginners.”

The two regional variations also feature differences in their production styles and the implements they use. Kamigata rakugo employs a small desk called a kendai, small wooden clappers called kobyōshi and a couple other devices, and it may be punctuated with shamisen, flute or taiko drum playing right in the midst of the storytelling.

“Performers might clack the kobyōshi against the kendai to add emphasis to movements or gestures, to give the impression of a scene change — or even to wake up audience members who’ve fallen asleep,” says Jinchi, cracking a smile.

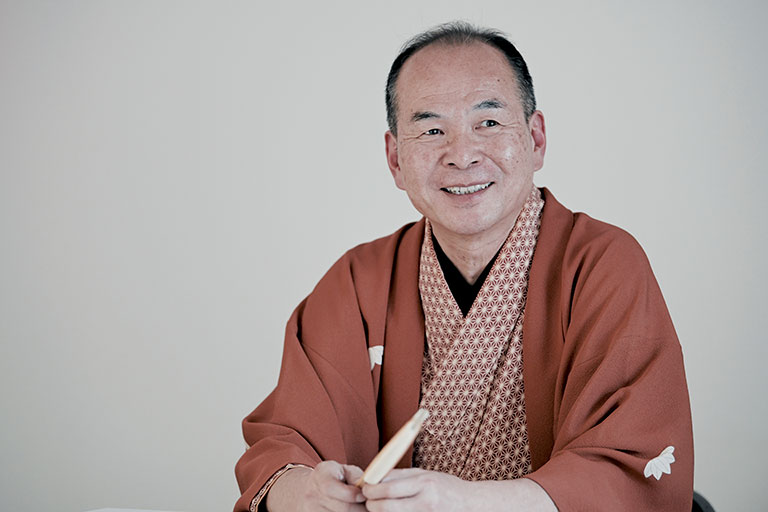

The Tenma Tenjin Hanjotei offers both matinées and evening shows. Matinées with eight performances are held daily, featuring everyone from young up-and-comers to veteran performers on a rotating weekly basis. Evening shows are then often organized by rakugo performers and offer solo performances, ichimonkai shows featuring performers from the same school or family group, and so on.

“The matinées feature a lot of programs that are like introductions to rakugo. The mood is easygoing, and I can recommend them to first-time viewers of rakugo. Then as you listen to their storytelling and find a favorite performer, or when a program comes up that looks interesting to you, be sure to stop in for one of the evening shows as well.”

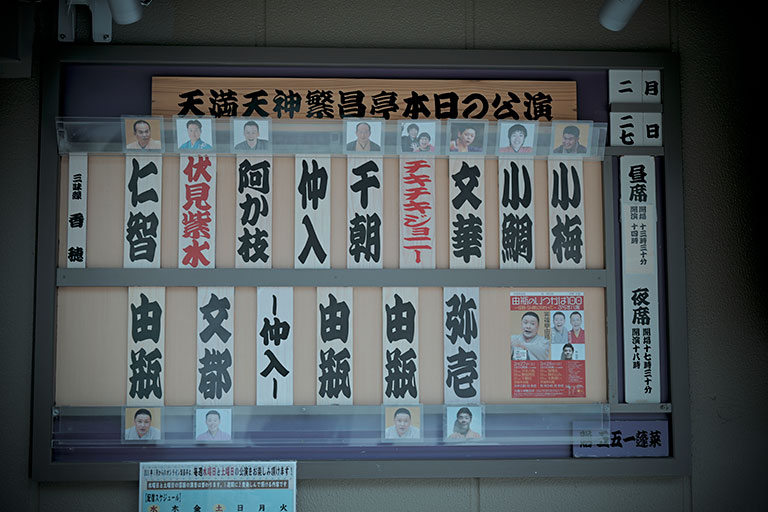

Taking in a Matinée at Last

A performer named Koume Katsura was the opening act on the day of our visit. Though unsurprising given the Osaka-based stage setting, his speech is peppered with a stream of Osaka dialect words and phrases: Egetsunai na (“Nasty!”), Akimahen (“Don’t!”), Sonna ahona (“Gimme a break!”)

Some Kamigata dialect that even locals don’t often use these days pops up too, and its jaunty tone is fun to listen to — to the point that it inspired the impulse to mimic it when the performance was over. (Be careful, though, as Osakans may tend to dislike it when others attempt to imitate the dialect in actual use!)

Next up was Kodai Katsura with a famous rakugo work familiar even to beginners, Toki Udon (“Time Udon”). Known as Toki Soba (“Time Soba”) in Edo rakugo, the work features not only a modified title, but a slightly different storyline as well.

During the performance it becomes apparent that laughing out loud in front of other people doesn’t always come naturally if you’re not accustomed to it, to a surprising degree. When an older man with the look of being a regular at a theater across the way gives an impeccable laugh at just the right timing, it’s hard not to be impressed in an as-to-be-expected way.

“Osakans take in rakugo with the intention of getting their full money’s worth in laughter. When audience laughter is boisterous, it helps the performer get into the swing of it too. The theater is a space created by the audience and performers’ shared experience of time,” explains Jinchi.

For this reason, performers often check out the vibe of the theater on the day of their show before deciding on their material. Pamphlets handed out to theatergoers accordingly list performers’ names but not program titles.

Jinchi had recommended, “When you come to the theater, just yield yourself to the performance, give your imagination full rein and enjoy the show,” and just in this way, the performance had the effect of drawing us in the audience in to the point of stirring our imagination as well.

As it so happened, the final performer of the matinée turned out to be Jinchi himself, and listening to his comical, adept descriptions of scenes was such an immersive experience that it brought a stream of mental images to mind.

The matinée featured eight performances in all. It seems that these always include two non-rakugo performances, and on this week, they were a manzai comedy act and a top-spinning presentation.

Before the show began, the program had seemed a bit long, but once it got underway, the two and a half hours went by in a flash.

After taking in a rakugo performance, visitors might enjoy taking a look around the Osaka neighborhoods providing the performances’ settings.

Information as of October 2021.

INFORMATION

Tenma Tenjin Hanjotei

2-1-34 Tenjinbashi, Kita-ku, Osaka

TEL: 06-6352-4874

Matinée: approx. 2:00 pm – 4:30 pm

All seats reserved: ¥2,500 in advance, ¥2,800 day of show

https://www.hanjotei.jp